What is PECS? | Learn from a Hopebridge BCBA Series

May 11, 2018

May 11, 2018

ASD, ABA, RBT, PECS, NET, DTT … how do you keep track of all these autism-related acronyms? If you have a child with autism spectrum disorder, you’ll likely hear dozens of letter combinations and new vocabulary over the next few years, starting as early as the diagnostic process. But what do they mean, and more importantly, what do they mean for your family?

We know there can be a learning curve that comes alongside an autism diagnosis, so we’re kicking off a monthly educational series to help simplify it. Hopebridge BCBAs (there we go again! “Board Certified Behavior Analysts”) will explain some of the commonly used terms and share details on what to expect during therapy.

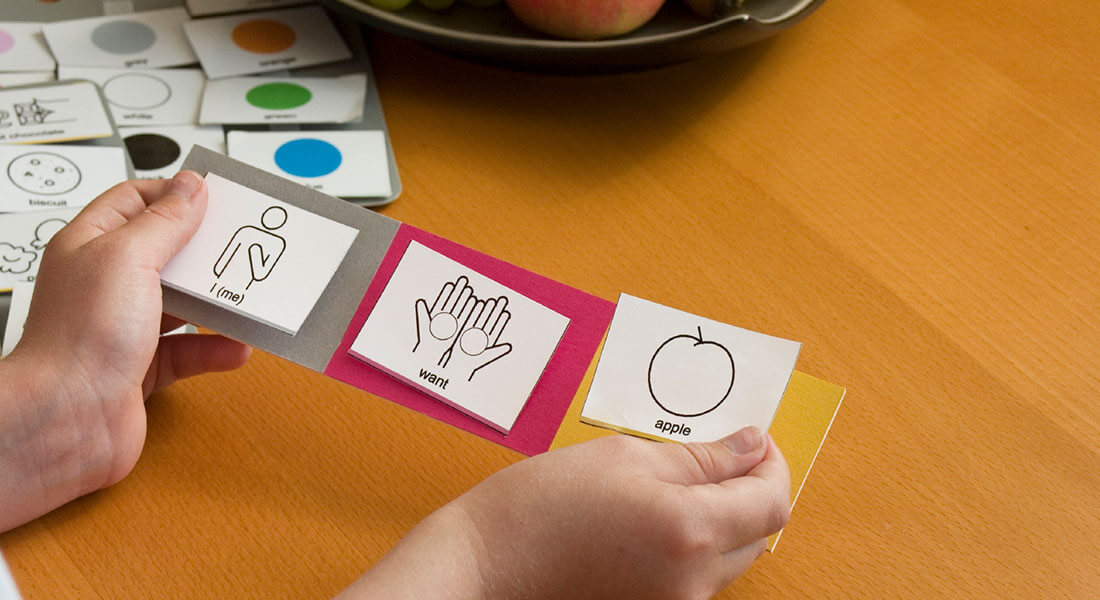

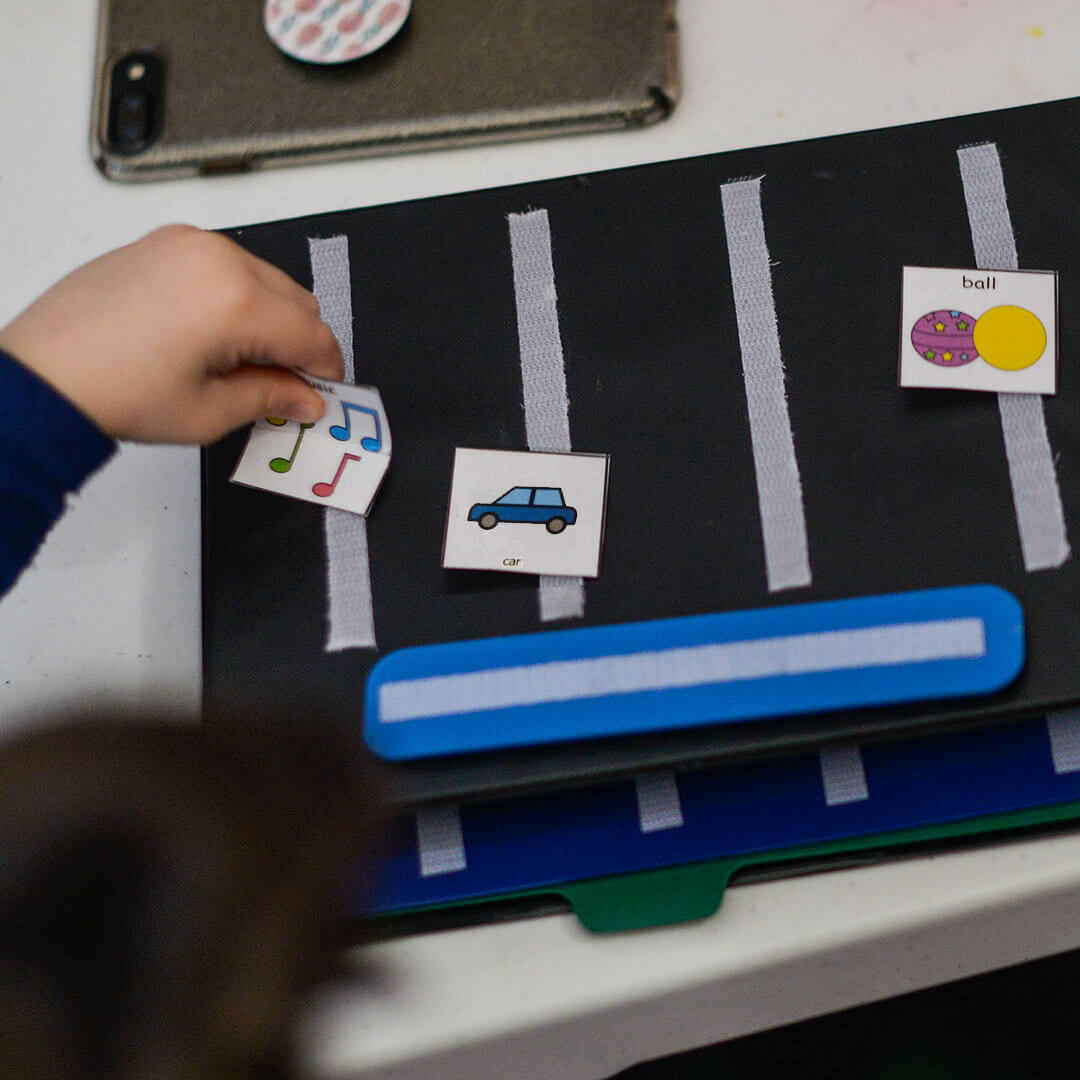

The PECS system can be a vital tool for non-verbal kiddos with autism.

Since many of our kids need a little extra help communicating, the series kicks off with Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS). Our hope for this post is to bring some comfort and understanding of the options that may be at your disposal if your child does not yet verbalize their wants and needs.

People new to or just learning about PECS often know that it involves pictures to communicate, but how it is used is more complex and meaningful. Developed by Lori Frost and Andy Bondy, the PEC system is a pyramid approach to education and is a form of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). In the most fundamental terms, this means a firm foundation must first be able to construct an entire body. In terms of forming language, this establishes that a non-vocal child must first learn the basics of language before becoming vocal or establishing a language system.

The PEC system establishes a six-phase program through which a child learns to communicate through building various skills in each phase, before adding an additional layer of comprehension. Each phase adds a new skill and new set of objectives the patient must acquire before moving onto the next set.

PECS uses pictures to help children with autism communicate their wants and needs.

PECS uses pictures at first, later moves onto words, and then to sentence strips for a learner to communicate not only his or her wants and needs, but also feelings, emotions and internal states, as well as engage in conversations. A key element is the PECS icon, which is a picture and the written word being depicted.

“PECS teaches so much more than simply speaking. It teaches children about taking turns, patience, self-advocacy, determination and persistency,” said Hopebridge Vice President of Quality Assurance Melissa Chevalier.

PECS is a six-phase system. In the first four phases, it is highly important to note that the listener (such as a teacher or parent) does not ask the child to exchange with them. Rather, spontaneity and motivation is what should establish the child’s asks; not a question, which may become a prompt.

PHASE 1:

In the first phase, the learner is taught “how” to communicate. The child is taught not only to approach a person to communicate their needs, but to use their own behavior to receive a wanted outcome. In this phase, a child is taught to pick up an icon (in early phases, a picture) of what is wanted and give that icon to the listener, who in turn gives the child what he or she requested.

It is important to label the request back to the child. For example, a child gives a picture of a cookie to the listener, the listener then says, “You want the cookie.” This is an important component as it begins the pairing process of words with receiving what they want.

PHASE 2:

In the second phase, the child learns to travel distance and to persist with his or her demand. This is done by gradually increasing the distance between the child and the PECS binder, as well as the distance he or she must travel to the listener. Once the child is traveling to and from the binder and listener independently, a greater emphasis is placed on the child persisting to obtain the listener’s attention. This can be done through tapping, making a vocal sound, reaching for the listener’s hand, etc.

PHASE 3:

The third phase teaches the child to discriminate amongst the PECS icons and is broken into two parts. The first part is to teach the learner to request (also known as “mand,”) and differentiate between icons that are reinforcing against those which are not. For example, an icon depicting a preferred toy and a picture of a napkin may be on the cover of the binder. Should the child choose and provide the listener the napkin, that is what he or she receives. If this is not what the child wants, rejection or maladaptive behavior may be exhibited. If the child takes the items and uses it, then it can be assumed the item is what they wanted. This is known as a correspondence check.

Once clear discrimination amongst preferred and non-preferred items are occurring, then phase 3B is introduced, which is conducted in the same way, except the child learns to distinguish between preferred items.

PHASE 4:

The fourth phase begins to focus on the sentence structure. In this phase, an “I want” sentence strip is added to the PECS binder and the child is prompted to chain the strip with the picture of what he or she is requesting. This is typically taught using backward chaining, as the child has already mastered the last step in the chain of putting the picture icon in the hand of the listener. At the end of this phase, the child should be successful in requesting at least 20 items across multiple settings with multiple people. Generalization is key to this form of communication being successful for the child.

PHASE 5:

In the fifth phase, we now teach the learner to respond to the question, “What do you want?” It is critical that we do not forget to create as many opportunities as possible for the child to request spontaneously as this can be quickly extinguished if we continually prompt their request. However, responding to this and similar questions is still important. For example, in a socially significant situation, it is important for a parent to ask and expect an answer to “What do you want to eat for dinner?” or “Where do you want to go?”

PHASE 6:

In the final phase, the child is taught to comment rather than only request. This is accomplished by adding varied sentence strips such as, “I smell,” “I feel,” etc. The same properties of discrimination training are applied as in previous phases.

PECS is typically utilized with children who have not developed vocal language by the age of 2.5-3 years old and are not responding to echoic prompts. If they are not closely trying to say words that are spoken to them, they may be good candidates to begin building language and communication skills via PECS.

That being said, a BCBA or speech pathologist may sometimes opt to use American Sign Language (ASL – here’s another one!) rather than PECS, depending on the child’s current skills. Typically, PECS will be used when a child does not have adequate fine motor skills (manipulation of fingers), or a strong imitation repertoire, meaning not only is the child not imitating words spoken, they are also not imitating other movements of the body.

Even when ASL is an option, a great benefit of choosing PECS is that the child is clearly understood, no matter who the listener may be. If, for example, a child needs help, and signs that to a peer, the listener will likely not understand. On the other hand, if a child hands the listener a sentence strip with the written words, “I need help,” there is almost no doubt the peer will then be able to ask a follow-up question.

The purpose of implementing PECS is to eventually (and hopefully) transition beyond it. As soon as a child begins to echo words or attempts to articulate the sounds they hear, separate articulation and echoic training should begin. However, PECS will not be removed until all the skills the child has learned through the communication system thus far in are also learned via vocal language, or via another preferred AAC device. To remove PECS before this would be unethical, as it would essentially remove the child’s ability to communicate.

Vocal language is continuously paired with PECS throughout a child’s programming. There is much evidence that PECS is highly successful in helping to develop vocal language more quickly than other communication program, and it is also typically the easiest program to fade once it begins.

When implementing PECS (and really, almost all forms of autism-related therapy and programs), make sure your child’s entire treatment team is on the same page. This includes teachers at school, ABA professionals, speech and occupational therapists, and most importantly, YOU! The best outcomes for children’s vocal language and other verbal language development stem from buy-in that comes from all parties. It does no good for your child to be using a device at school, ASL in speech, PECS while at ABA sessions, and pointing and gesturing at home. If everyone uses the same system, your child will learn more quickly and the system will be more effective.

No matter what system of communication is used, ensure that you, as the parent, are 100% aware of what is being taught so that you may work on it at home.

“If you practice your child’s language with them in the same way, your child is going to learn so much faster, and the rewards for both of you will last a lifetime.”

“You likely spend more time with your kid than anyone else and serve as their biggest reinforcer,” said Melissa. “If you practice your child’s language with them in the same way, your child is going to learn so much faster, and the rewards for both of you will last a lifetime.”

Beyond that, don’t be afraid. Ask questions and do your research. PECS has the greatest outcome for children who move from completely non-vocal to speaking than any other program to date. Your team of BCBAs, SLPs and RBTs are your first one-stop-shop on learning how to benefit from this system. They are there to not only help your child, but also to help you learn more about it, dispel the fears and myths, and above all, develop a deeper relationship with your child.

At Hopebridge, it’s important to us that you and your child have a way to effectively communicate with each other. Our clinicians are here to give our kids the tools to build the skills that will set them up for a lifetime. If your child is non-speaking or could use more support in communication or other developmental areas, reach out to us to discuss the options and services available to you.