What is an AAC Device and How Does it Enhance Communication?

January 13, 2022

January 13, 2022

From the moment their babies are born, parents wish they could mindread. Knowing when infants want to eat, sleep or have their diapers changed – or any other reason behind their cries – would certainly make things a lot easier! As they get older, many families of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) crave this superpower even more, especially if their children are nonverbal. As difficult as it is for these parents to wonder what their kids are thinking or feeling, imagine how much these children must wish their desires could be understood.

The good news is, while we don’t have a magic key to reach their thoughts, we do have tools and strategies to help them express themselves in other ways. You can communicate with your child, even if they don’t yet speak. We just need to discover the method of communication that works best for them.

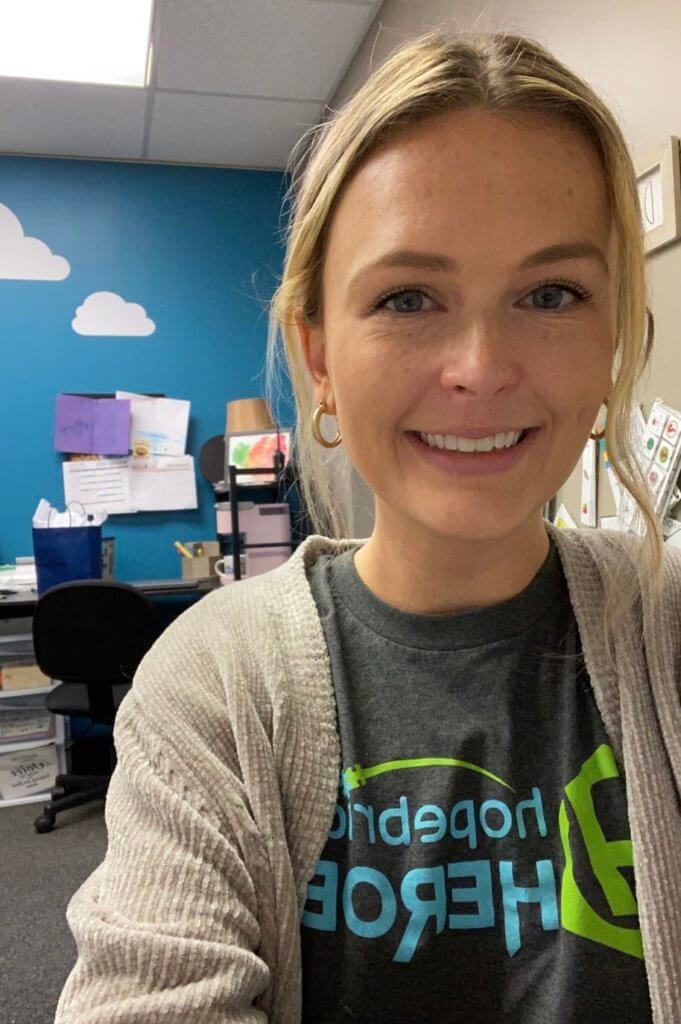

“This is why I love AAC. It’s my biggest passion because it gives these kids with autism and other developmental delays more freedom,” Hopebridge Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) Hayley Brodt told us from our autism therapy center in Middleburg Heights, OH.

To find out more about AAC devices and how they can be used to enhance communication, we asked Hayley to break down the details for us:

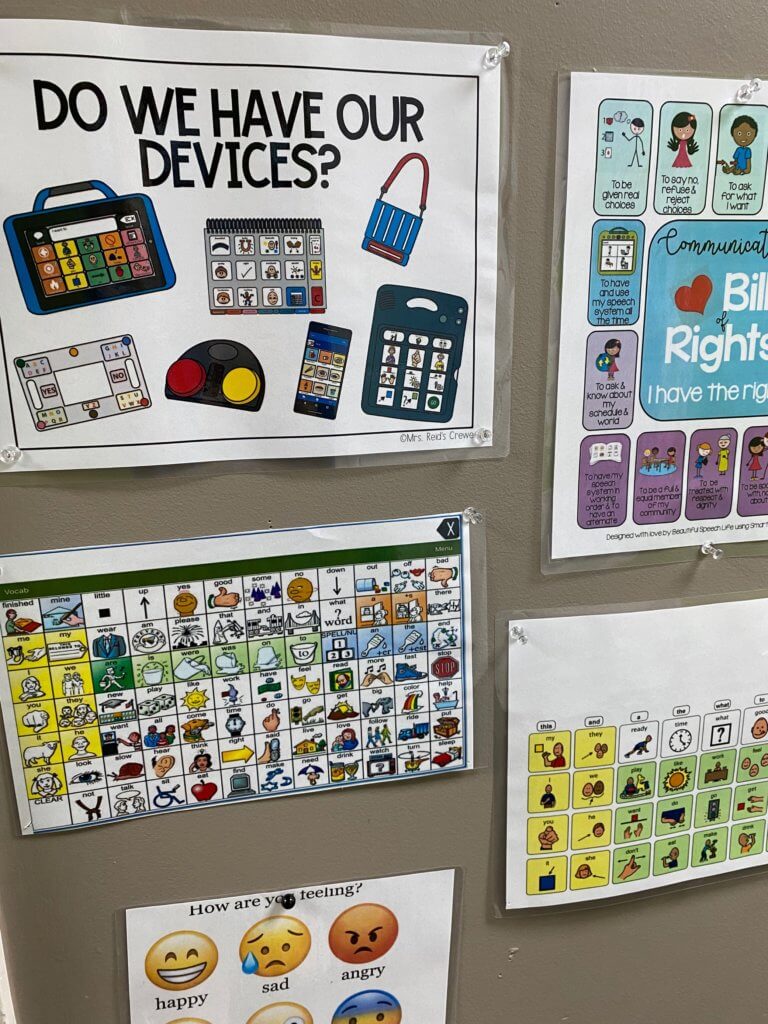

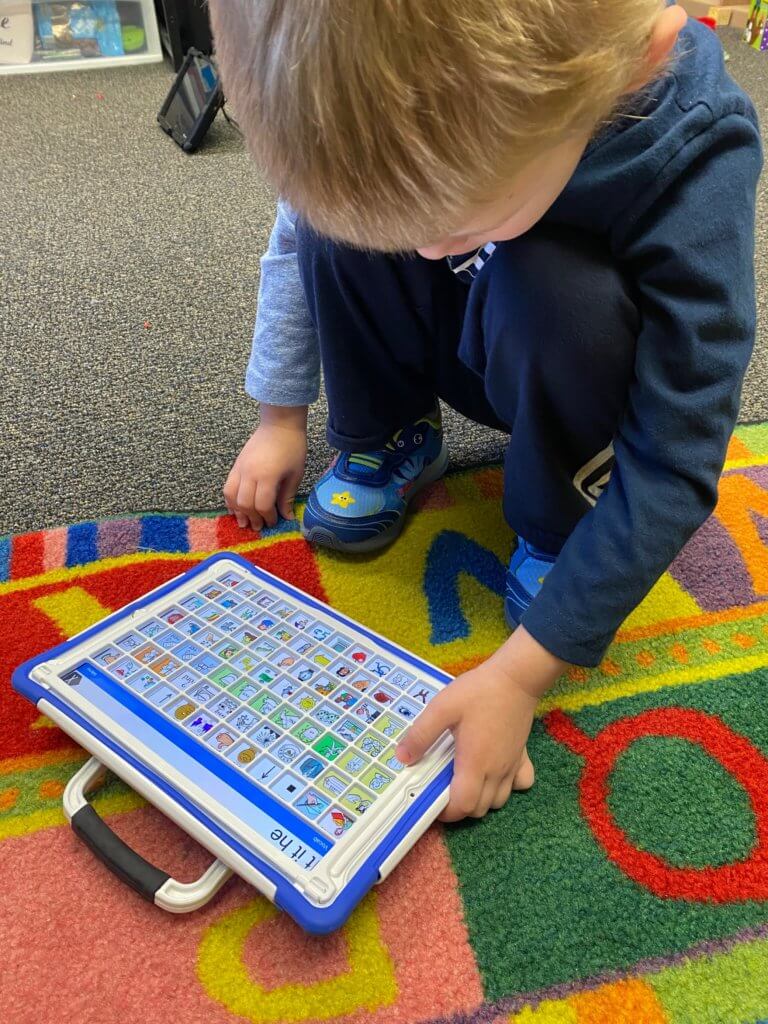

You may be thinking, “But what does AAC mean?” An augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) system helps individuals increase their communication by adding to their current ability or serving as a different form of communication than speech. There is a broad range of AAC devices from no-tech and low-tech to high-tech. It can be anything from a gesture, to a piece of paper with a word or picture on it, to a digital tablet programmed to serve as a voice.

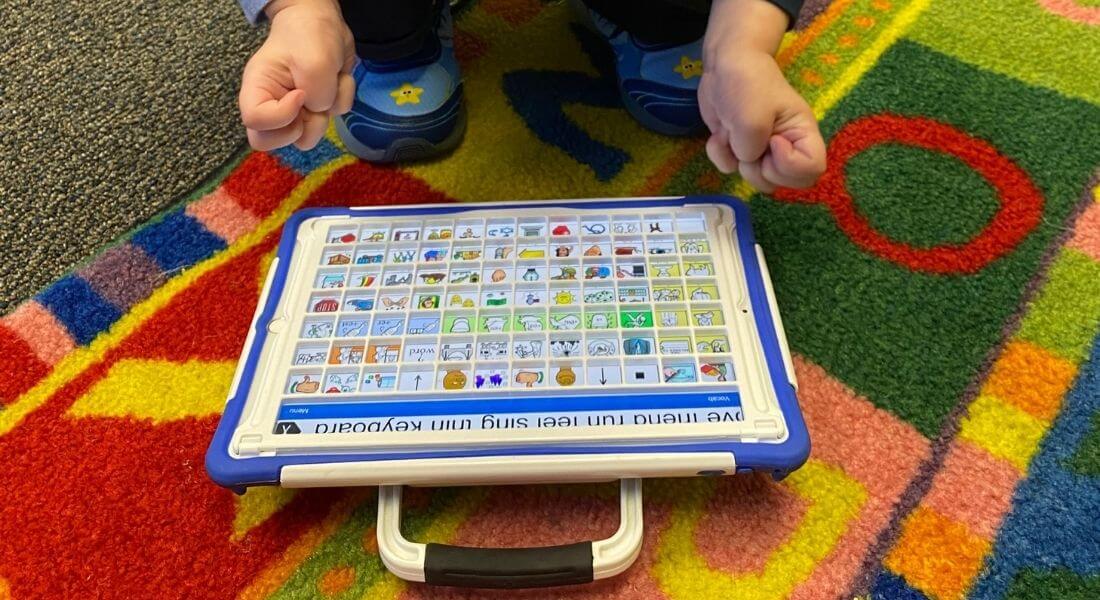

It’s common to see core boards used as AAC around our Hopebridge centers. This type of AAC device is a laminated piece of paper that includes core vocabulary. It can be a picture of what is found within one of the high-tech systems, or it can be something simple our therapists create internally. The Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) is another type of low-tech system that is commonly used.

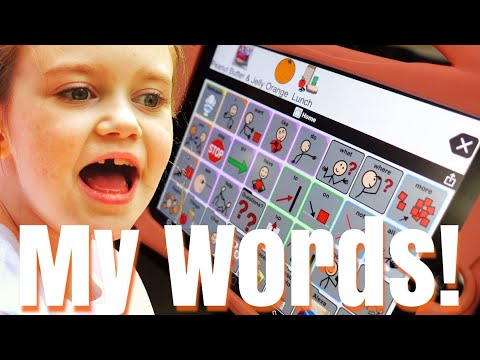

One of the commonly used high-tech options is LAMP (Language Acquisition through Motor Planning) Words for Life, which is an app that can be used on various tablets. The buttons have pictures and the corresponding words on them. I like it because it’s based on motor planning, so the buttons never change locations, much like the keyboards on our laptops and phones. The user learns where their finger goes and eventually it will become automatic, just like speech is automatic. We want whatever they use to feel effortless and natural, and LAMP has the ability to make that happen.

At Hopebridge, our SLPs work with each child to see what works best for them and their individual needs. Core boards can be used immediately, so we usually start with them even for those waiting to use a high-tech device.

There are so many benefits to using AAC, but it is unfortunately often misunderstood, so I want to address some of the common AAC misconceptions and concerns:

Myth #1: AAC Devices are only for nonverbal children.

One of the great things about AAC is that any child can be a good candidate for it; it is not only limited to non-speakers. In my experience, if I provide a kid who is speaking with a core board, it only allows them to talk even more. It gives them the visual representation to express what they want and their ideas. Even if a child is verbal, maybe they can’t find the words or it’s effortful to do so. Or, maybe a child – or an adult – becomes upset and is unable to explain what is going on. We could provide a visual of emotions that the individual can point to in order to share how they’re feeling, such as “I’m sad.” Other individuals might find a high-tech device beneficial to use if they experience social anxiety around others.

Myth #2: My child will not learn to speak if they use a device.

Research shows AAC will not stop a child from speaking, nor will it slow down language. Oppositely, if there is any change in verbal language development, it typically increases or helps them develop speech faster than they would have without the use of AAC.

Myth #3: Using an AAC device with my child will be too difficult.

AAC can be intimidating at first glance. People new to AAC might think, “I don’t know how to use it, so how am I going to talk to my kid with it?” I like to explain it this way: Think about a new baby. We don’t expect them to come into this world chatting right away. It’s the same for us. We need to be patient and make an attempt. If we don’t try to use the system, neither will our kids. Take a chance to explore it! It won’t hurt anything. If you hit the wrong button, use it as a learning moment and say, “Oops, sorry, I made a mistake and am going to go back,” just as we would with our own speech. Plus, Hopebridge offers parent training to help families navigate the process.

Myth #4: Once they start using AAC, they’ll have to use it forever.

Nothing is set in stone. When a child does start talking, they don’t need to keep the device. We can stop using it unless they find it helpful in certain situations. The great thing about our interdisciplinary programs at Hopebridge is that we are also in constant communication with the Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBA). If we feel another system might work better for one of our kiddos, we’re able to collaborate with them and families to make those adjustments.

How we implement an AAC device depends on the child and what type of device they are using. It’s not complicated, but it helps to have support from an SLP.

There are no pre-requisite skills necessary to use AAC. In terms of cognitive development, even if a child does not yet understand cause and effect, we can use an AAC system to teach it to them: “when I use this, I get what I want.”

If they are unable to point or have challenges around motor skills, there are other ways to access these devices for communication. For example, there are key guards that can be traced until their finger is in the desired location. If they cannot use their arms, they can hit a switch. There is even eye gaze technology, in which they can use their eyes to track the words, phrases or pictures of choice.

When using high-tech systems, we can choose different levels. We can start with one page of choices, but as the child increases communication skills, the screen opens up to additional pre-made phrases. For instance, if the child chooses “I” on the first screen, a new page of options will open to suggest phrases such as, “I want,” “I don’t want,” “I like,” “I don’t like,” and “I feel.”

While I introduce a high-tech device, like an iPad with a communication system like LAMP, I first print and laminate the initial screen. I use this as the patient’s core board while they wait for the device in order to keep it consistent.

Then, I would model the action by teaching it in everyday context. For instance, if I knew my patient wanted something, like a book, I would hold onto the book, and as they reached for it, I would say, “I want,” and touch the “I” and “want” buttons or spaces on the core board. I then show the device to them. Maybe they will repeat the action or maybe they won’t, and that’s ok because they’re still learning. Then I give them the book. Walking down the hall, I would do the same thing. I’d touch “stop,” hold their hand to stop, and say, “We stopped. What do you want? Do you want to go?” Then touch “go.”

While it seems simple, this type of communication is incredibly impactful. Our parents are so excited once they use it because now their child is able to say things like, “eat,” “go” or even more complex sentences like, “I don’t want to be here, let’s go.”

These devices are life-changing.

For kids who do not yet use their voices to speak, having visual support to express themselves can be so beneficial. It helps teach consent, as kids can now say when they don’t want something, or can tell a teacher or a parent if something happens at school that upsets them.

I saw one child for therapy who struggled with apraxia of speech, which is when an individual’s brain knows what it wants to say but their mouth can’t say it. I gave this boy a device and his face lit up right away. He was such a bright kid and could already read, so after showing him how to use it one time, he was able to communicate with it immediately.

This boy didn’t like circle time at the center. One day, he heard someone ask me over the walkie talkie whether he was coming to circle time. He looked at me and used his device to say, “no circle.” I was so proud of him for expressing himself that of course I didn’t make him go! I told him he never had to go to circle time again.

It was one of those perfect moments when it all clicked. All I had to do was give him a communication system and he flourished. He’s since graduated from Hopebridge and I transferred the device to the school so he can continue to communicate effectively in the classroom.

AAC is a great tool even for those who are verbal. Think of when you’re upset or frustrated and can’t think of the words to say … How do you handle those situations? Personally, I sometimes write down or type out my thoughts, and when I calm down, I can read them to someone, or I might already feel better after the act of writing out the words. AAC offers the same for kids who are visual learners. If there’s a picture of what they want or how they’re feeling, it might be easier to express themselves this way than to say it out loud.

Before I worked at Hopebridge, I worked at a special education school and saw a teenager for speech therapy. He could speak, but his talking consisted of scripting; repeating things he heard on TV or at school. I trialed a device for him, and for the first time, he was able to actually communicate his own thoughts rather than imitating others. It was a life-changing shift for him and amazing to see him open up.

Above all, if your child is having a difficult time communicating, I encourage parents to be open to the idea of AAC. Even if your child is talking, there are always ways to supplement that.

When something is new and we don’t know a lot about it, it can feel scary at first, but there’s no harm in giving it a shot. Bring it up to your SLP and ask if it’s an option for your child. It can open up a whole new world for them, while allowing you a peek into theirs.

Hopebridge is here to help your child find their voice. From speech therapy and occupational therapy, to diagnostic assessments for autism and applied behavior analysis (ABA), we are here to provide support throughout your family’s autism journey. Fill out our easy form to start the conversation about creating a personalized plan that meets the needs of your child.

*Informed consent was obtained from the participants in this article. This information should not be captured and reused without express permission from Hopebridge, LLC. Testimonials are solicited as part of an open casting call process for testimonials from former client caregivers. Hopebridge does not permit clinical employees to solicit or use testimonials about therapeutic services received from current clients (Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts 5.07-5.08; BACB, 2020). Hopebridge does not provide any incentives, compensation, or renumeration for testimonials provided by a former client or client caregiver.

Parenting Resources

October 29, 2024

A Guide to Understanding an Autism Diagnosis and Documentation

Parenting Resources

November 27, 2024

BCBA-Approved Toys for Learning and Development During Cyber Week 2024

Parenting Resources

September 20, 2022

Is Your Child Ready for School? 5 Signs to Consider